Laboring for a Cure to Infertility

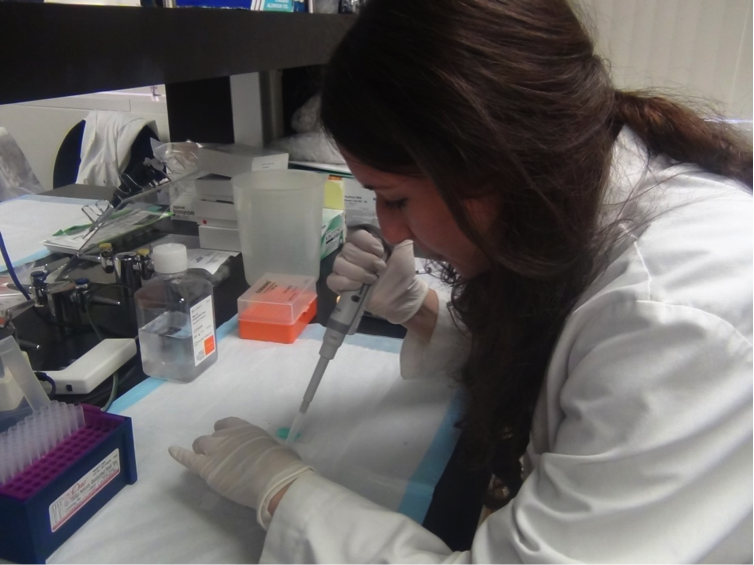

Ariela Agress, LCW '12, spent the past summer researching the cure to infertility.

This past summer, while other young women her age might have been relaxing at the palm-tree-lined beaches of the Pacific coast, Ariela Agress—a 2012 graduate of the Lander College for Women-The Anna Ruth and Mark Hasten School—was searching for the etiology of PCOS, otherwise known as polycystic ovary syndrome.

The 23-year-old Lander College for Women (LCW) alumna is a second-year medical student at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California Los Angeles, one of the top ten medical schools in the country. This summer, she landed a research assistant position in Dr. Daniel Dumesic’s Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility Lab at UCLA.

PCOS, a disorder of reproductive age women, is related to an excess production of testosterone, irregular ovulation, and ovarian cysts. The disorder is one of the most common causes of infertility and affects nearly five million women in the U.S. Yet although the heterogeneous syndrome is associated with numerous other conditions (such as obesity), the primary cause of PCOS is unknown. And so, treatments are always directed at the symptoms of the disorder—in this case, infertility. Under the instruction and supervision of Dr. Dumesic, Agress is helping his team test the hypothesis that women with PCOS store lipids in tissues where they shouldn’t be, and that these misplaced lipids may cause a sequence of events that impact the function of the ovary.

“I just incubated the adipocytes with fluorescent antibodies,” a cheerful Agress declares as soon as she greets the author in the Student Garden outside the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, “so I have an hour to talk.”

Agress, who was awarded both the Chemistry and Biology Awards upon graduating from Touro’s Lander College for Women in 2012, says that her alma mater’s pre-med curriculum was rigorous enough for her to be challenged academically—and eventually help her get accepted to UCLA.

As one of five women in LCW pursuing medical school, she initially regarded her small cohort of pre-med peers as a disadvantage, but quickly realized how beneficial it was to her in the long run. Because there were only a handful of them, each pre-med student was able to take a leadership role in the school. This, says Agress, ultimately provided her a competitive edge in the admissions process. After serving as president of the Pre-Med Club during her sophomore year, she also decided to coordinate the LCW Blood Drive Campaign. She collaborated with New York Blood Center to organize the logistics of each blood drive and recruit donors, resulting in “hundreds of lives being saved.”

She also appreciated that the close-knit college helped her develop close relationships with her biology and chemistry professors. “Since it was a fairly small college, I really had the chance to get to know each one of the professors individually—which made a big difference in my recommendation letters. Many of my professors served as excellent mentors, with whom I still keep in touch.

She was active outside school as well. During her years on the Manhattan campus, she volunteered for Chai Lifeline and Roosevelt Hospital, also spending time shadowing a surgeon in St. Luke’s Oral Surgery Unit. One summer, she interned at the Medical Genetics Lab of Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

As we head into the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ariela puts on a lab coat and pulls up her gloves. Skimming over her lab notes, she picks up the pipette. Her passion for her lab work is apparent as she works methodically but cheerfully, oftentimes humming or explaining things as she goes along.

“Sometimes the routine becomes repetitive, but the overall concept of the whole process is so rewarding—we’re ultimately trying to help women have children—that it brings me back here excited every day,” she said.

When Agress was deciding what career path to take at LCW, she worried about the challenge of balancing medical school and a future family, but ultimately decided to go for it anyway.

“I’m so glad I took the plunge,” she emphasizes. “There is no other place I would rather be.”